On 20 December 2013, the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA), located in The Hague, Netherlands, announced its Final Award on the Indus Waters Kishenganga Arbitration. This dealt with a dispute between Pakistan and India, related to India's proposed 330 MW Kishenganga Hydro Electric Project (KHEP) in the Baramulla district in Jammu and Kashmir. Pakistan had objected to the construction of the KHEP, contending that it adversely impacted Pakistan's own Neelum-Jhelum Hydro Electric Project (NJHEP), which is downstream of the KHEP.

The Award has allowed India to build the KHEP as designed, but also put certain restrictions on the project. Being an India-Pakistan dispute, the Award naturally received a fair bit of media coverage, including claims by each side of a victory. Certainly, the Award is important insofar as the KHEP project is itself concerned. But far more important is the decision of the PCA that requires the KHEP to release certain minimum "environmental flows" at all times of the year. This decision, which has gone beyond the terms of the Indus Treaty – has far-reaching implications.

The Jhelum River in Pakistan. Pic source: Wikimedia

The Indus Water Treaty

The Indus Waters Treaty (IWT) was signed in 1960, but it was preceded by a bitter dispute between India and Pakistan that began immediately after partition and independence, in 1948. At the time of partition, the Indus river system – consisting of the Indus River itself, and its five major tributaries, Sutluj, Beas, Ravi, Jhelum and Chenab – had highly developed irrigation systems. Partition cut through the rivers and irrigation systems, making India the upstream state and Pakistan downstream for all the six rivers.

While the initial attempt to resolve the dispute involved working out a mechanism to jointly manage the rivers, irrigation and hydropower systems as a unified whole, that was not to be. The IWT resolved the dispute by creating a unique arrangement. The entire waters of the three "eastern rivers" – Sutluj, Beas and Ravi – were given to India, and the all waters of the three "western rivers" – Jhelum, Chenab and Indus – were given to Pakistan.

However, there were important exceptions under which India was permitted some use of the western rivers, in particular, the construction of hydropower projects on these rivers, subject to some constraints. The Kishenganga project is possible because of one of these exceptions granted to India.

KHEP and NJHEP

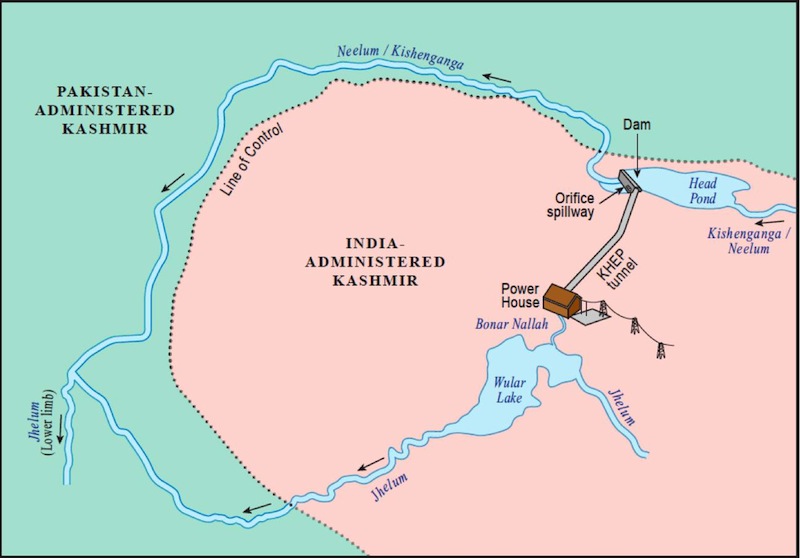

The Kishenganga River, a tributary of the Jhelum, crosses the Line of Control from India into Pakistan where it is known as the Neelum. The KHEP is proposed as a run-of-the-river plant. (This does not mean a true run-of-the-river project. The KHEP will have a storage, and more important, will divert most of the water of the river away from the river channel). It will have a 37-m high dam, and will divert the waters of the river into a stream called Bonar-Madmati Nallah through a 24-km-long tunnel.

The Bonar nallah meets the Wular lake, from which the Jhelum flows into Pakistan. The Jhelum receives the Neelum River downstream of the Wular. Thus, the waters of the Kishenganga / Neelum get diverted from the main river but through a roundabout route, reach Jhelum as they did earlier.

The only problem is that the stretch of the Kishenganga / Neelum below the KHEP will have lesser flow till it meets Jhelum. It is precisely in this stretch that Pakistan has planned its 969-MW NJHEP. The NJHEP is located at Nauseri, about 158 km downstream of KHEP. It has a 41.5-m-high dam, and diverts water through a 30-km-long tunnel into the Jhelum river.

The images below show the projects and the rivers schematically. (Source: Partial Award of PCA)

The Dispute

Any diversion of waters away from Kishenganga at KHEP would impact the generation at NJHEP. Pakistan objected to the KHEP saying that it "breaches India's legal obligations owed to Pakistan under the Treaty, as interpreted and applied in accordance with international law, including India's obligations under Article III(2) (let flow all the waters of the western rivers and not permit any interference with those waters) and Article IV(6) (maintenance of natural channels)". This was the so called First Dispute framed by the PCA.

The Second Dispute related to whether "India may deplete or bring the reservoir level of a run-of-the-river plant below Dead Storage Level (DSL)", an issue that we will not focus upon in this article. (The PCA ruled against it and against India in this matter).

However, India had a strong case, as one of the provisions of the Indus Treaty itself explicitly allows a KHEP-type project. This is the Clause 15 (iii) of Annexure D, which states that if a Plant is located on a Tributary of the Jhelum which Pakistan uses for any agricultural or hydroelectric purpose, the water released below the Plant may still be delivered into another Tributary, if necessary. However, this may be allowed only to the extent that the then existing agricultural use or hydroelectric use by Pakistan on the former Tributary is not adversely affected.

Pakistan moved the PCA on 17 May 2010, and after long-drawn proceedings including field visits, the PCA rendered its Partial Award on 18 February 2013. This Partial Award ruled that the Clause 15(iii) cited above allowed India to build the KHEP as designed, diverting water into another tributary of Jhelum. It also made a finding that "that there are no significant existing agricultural uses of the Kishenganga/Neelum's main river [in Pakistan]. It appears to the Court that agricultural uses in the Neelum Valley are largely met by the tributary streams that feed the river".

The PCA also noted that while Pakistan mentioned plans for future agricultural development based on the Neelum waters, "it had been unable to provide a quantitative estimate of the likely scale of such development".

On the "then existing hydropower uses", the PCA found that both in intent and in implementation, India's KHEP came much before Pakistan's NJHEP; thus, for the KHEP, the NHJEP could not be termed as an "existing use". Therefore, the PCA found that the restrictions to Clause 15(iii), namely that the waters could be diverted into another tributary of Jhelum only to the extent that "then existing agricultural or hydroelectric use" of Pakistan would not be affected, were in effect non-existent. KHEP was thus freed of all constraints and allowed to divert water into another tributary.

However, after freeing KHEP of all constraints imposed by the Treaty, the PCA introduced a new one – the need to allow flows below the KHEP for the protection of environment downstream.

The Environmental Flow Requirement

The PCA, in its Partial Award, states that apart from the needs mentioned in Clause 15 (iii) - from which it effectively frees the KHEP –"India's duty to ensure that a minimum flow reaches Pakistan also stems from the Treaty's interpretation in light of customary international law."

Now, the Indus Water Treaty itself acknowledges that international customary law can be used, but imposes severe restrictions on the situation and the extent to which customary law can be applied. Clause 29 in Annexure G states that "... the law to be applied by the Court shall be this Treaty and, whenever necessary for its interpretation or application, but only to the extent necessary for that purpose, the following in the order in which they are listed: (a) International conventions establishing rules which are expressly recognized by the Parties; (b) Customary international law"

This means that customary law can be used only for the purpose of interpretation and only to the extent necessary to interpret the Treaty. With Clause 15(iii) so clear and unambiguous, there was little need for the PCA to use customary law for any interpretation.

Yet, the PCA has taken the very important step of bringing in the use of customary law, even by going beyond the provisions of the Treaty. It has done this by interpreting the larger canvas within which such Treaties are adjudicated upon and implemented.

Firstly, the PCA notes that the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, 1155 U.N.T.S. 331 requires that apart from the provisions of the Indus Water Treaty itself, the PCA has to take "account of relevant customary international law—including international environmental law—when interpreting the Treaty". Therefore, the PCA holds that it is bound to take account of relevant customary law (the unsaid part of this statement being "even if the Treaty itself restricts such a use of customary law").

Second, it brings out several judgements and international case laws to show that "It is established that principles of international environmental law must be taken into account even while (unlike the present case) interpreting treaties concluded before the development of that body of law." It also establishes that "Well before the [Indus] Treaty was negotiated, a foundational principle of customary international environmental law had already been enunciated in the Trail Smelter arbitration. There, the Tribunal held that no State has the right to use or permit the use of its territory in such a manner as to cause injury by fumes in or to the territory of another." This is the "no transboundary harm" principle.

Based on this, the PCA ruled that the KHEP could not divert all the waters from Kishenganga, and Pakistan had a right to require KHEP to release some minimum flow all through the year to ensure protection of the environment downstream. It then asked the two countries to present their own recommendations for such an environmental flow, heard the matter again and then gave its Final Award in December 2013 where it determined the minimum flow releases of the KHEP.

Environmental Flows

Pakistan used a fairly sophisticated and detailed method called Downstream Response of Imposed Flow Transformations (DRIFT) to recommend releases of between 20-40 cubic meters per second (cumecs). India used what is called a hydraulic rating method using a cross section of the river and working out the water levels for various flow rates, and looking at levels that are necessary to be maintained to ensure survival of three species of fish.

The latter is a fairly limited method, particularly compared to the DRIFT methodology, but is much more that what India is doing for projects within our own boundaries. For example, in the Lohit Basin in Arunachal Pradesh, the environmental flow assessment uses a totally ad hoc method where an arbitrarily assigned percentage of the flow is suggested as environmental flow. For Kishenganga, India said that even a flow of 2 cumecs would suffice.

However, while giving environmental clearance to the project, India's Ministry of Environment and Forests had, independently of the arbitration proceedings, recommended an environmental flow of 4.25 cumecs (though the logic of this recommendation is not clear either). Using these as basis, the PCA specified that KHEP should maintain a minimum environmental release of 9 cumecs.

There are many problems with the Award. First of all, as the PCA itself notes, the notion of environmental flow is broader and more comprehensive than that of minimum flows. Moreover, the determination of the figure of 9 cumecs is also fairly ad hoc, but it should be seen in the context that the arbitration was not an exercise in determining environmental flows. Rather, it was an attempt at resolving a dispute within the provisions of the Treaty. Given this, the PCA was pushing the envelope in introducing environmental flows and was overly bound by the requirements of the Treaty.

Even as we need to look at the environmental flows part of the Award critically, it is an important step forward, with several implications.

|

Implications

First of all, the PCA Final Award has, in interpreting the Treaty, provided important guidance that customary law must be taken into account. Particularly, the law of "no trans-boundary harm" is critical. However, the nature of this law itself is such that the "boundary" in question need not be an international boundary. It can be boundaries of states within a country, and indeed, the most important boundary in this case is the dam itself.

A dam on a river forms the boundary between upstream and downstream, and in every such case, the law of "no transboundary harm" must be invoked; that is, we cannot allow such projects to cause harm downstream. Thus, while the PCA ruling may have come in an international context, it is directly relevant in the national context too.

What is interesting against this background is the emphatic statement made by India to the PCA during the hearing of the matter. India's Agent, the Secretary to the Ministry of Water Resources, said: "So I would like to first assure the court that there will be a minimum environmental flow, and that will be in accordance with our laws ... "I assure the honourable court that we can't leave our territory dry; and since we can't do that, by consequence we can't leave any of Pakistani territory, which comes later on, dry."

When the Secretary, Water Resource Ministry gives a solemn assurance that "we can't leave our territory dry", we can only hope that this will apply to all projects in the country too, and not just international projects. Unfortunately, we have tens of KHEP-type projects in our own states of Arunachal, Uttarakhand, Sikkim, Himachal, where cascades of so called run-of-river projects are diverting almost the entire waters of the rivers into tunnels, leaving long stretches of the rivers dry and the environment severely affected.

The Kishenganga Award reinforces the need to provide environmental flows in these rivers, and also using detailed and comprehensive methodologies like DRIFT, which falls under a class of methods called Holistic methods, in doing so. Thus, even as India claims victory in the Kishenganga dispute with the Final Award of the PCA, it is necessary for us to understand and accept the more fundamental and innovative part of the Award. Using that, we should move to introduce a regime of environmental flows in all our rivers through a scientific and participatory process.