Over the ages, India has largely reduced Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to a paper face that holds little or no meaning for the millions of Indian children who do not know anything about him and identify him only with that picture on the currency note. Thankfully, however, contemporary Indian cinema has restored dignity to the Mahatma by liberating him from the confines of that portrait and bestowing upon him the respect that is due through biographic and innovative fictionalized accounts.

The first fictionalised biopic was Gandhi (1982) directed by Richard Attenborough in which Ben Kingsley, a half-Gujarati who grew up in England, played Gandhi. The film tracks his life from the time he was thrown out of a train in South Africa meant exclusively for “whites” till his assassination in 1948. Though the film fetched good reviews and won awards, the industry fraternity was critical about the NFDC allowing a very generous grant to a foreigner to make a film on Gandhi.

Times have changed. So have the average Indian filmmaker’s perceptions about Indian history. Gandhi seems to be omnipresent in many recent Indian films in terms of ideology, metaphor and essence, if not in terms of physical presence. A considerable number of films have been made either on Gandhi himself or using Gandhi as a symbol, an ideological concept or even as a ghost in Lage Raho Munnabhai!

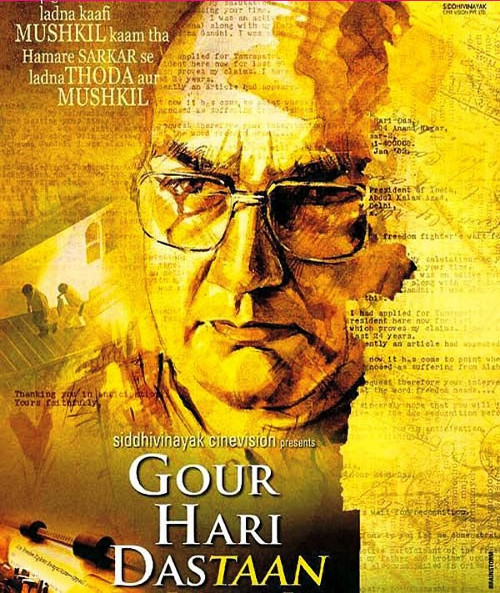

A poster of Gour Hari Dastaan - The Freedom File. Pic: Ananth Mahadevan

The latest in this long line of films upholding the honesty and integrity that the Mahatma stood for is a biopic on a living Gandhian in his eighties. His name is Gour Hari Das. The name of the film is Gour Hari Dastaan – The Freedom File, made by actor-director-scriptwriter Ananth Narayan Mahadevan. Mahadevan chronicles the struggle of this Gandhian whom he has met in person. These interactions, believes Ananth, have enriched him as a human being.

“The country does not recognise the value of freedom that was hard fought and came at a price that was bloody. A generation has not been exposed to the truth of how their houses came to be built – and the roof over their heads,” says the director in a tag-line for his film.

Was the bloody price people like Gour Hari Das paid really worth it? Has ‘freedom’ in its true sense, really been achieved? The film traces the evolution of ‘freedom’ through the struggles of Gour Hari Das.

But who is Gour Hari Das and how did he become the subject of an entire film? Gour Hari Das, during his teenage years, got involved in the struggle for independence in Balasore, Orissa where he was growing up. He was enrolled in Gandhi’s vanar sena for younger freedom fighters. His work was to courier messages and letters between and among freedom fighters by running alongside rushing trains to hand over the letters. He was 14 then and was arrested and imprisoned for three months.

“I read about Gour Hari Das in a tabloid. The headline screamed, "It took him 32 years to prove that he is a freedom fighter.” The irony was there for all to see. I probed further and tracked him down to a distant suburb of Mumbai...Dahisar,” says Ananth Narayan Mahadevan who also co-produced the film along with Bindiya and Sachin Khanolkar.

Director and co-producer Ananth Mahadevan on the set of the movie. Pic: Ananth Mahadevan

The Das family later migrated to Mumbai and settled in Dahisar, a Mumbai suburb. He still lives an austere Gandhian life with his wife Lakshmi. The story of his life is significant because one day, around the mid-seventies, his son complained that he was being refused admission under the quota for freedom fighter’s wards, because he could not produce any proof that his father was a freedom fighter. Das suddenly realised that it had never occurred to him that he was not given theTamra Patra every freedom fighter is entitled to because he had not really fought for any award.

He is speechless with shock when his son turns around and asks him, “Were you really a freedom fighter?” Something ticks inside him and his new fight for another ‘freedom’ begins. He embarks on a journey to find proof that he was indeed in jail for three months, that he was really a freedom fighter, that he was a genuine member of Gandhiji’s vanar sena and that he was a true Gandhian who did not believe in rewards for fighting for his country’s freedom. It was only the Tamra Patra he was entitled to that could provide this proof..

His son was not in the picture anymore, but Das wanted to get his proof. It took him 32 long years to finally be given the Tamra Patra – now on a piece of paper by the Maharashtra CM himself. In these 32 years, the director informs us that Das had to knock on 321 doors, wrote 1043 letters to different officials, climbed 66000 steps, pleaded 2300 times in Post-Independent India to prove that he was the freedom fighter who was once blessed by Mahatma Gandhi and was jailed for fighting against the British. He visited government offices, influential politicians, ministers, media, jail officials etc. During this turbulent journey, he was labelled 'fraud', 'thief', 'crazy', 'eccentric' by various people.

Vinay Pathak, a gifted and trained actor of Bollywood, who was chosen to play the title role says, “In 2008, Gour Hari Das was front page news. The Maharashtra Government had just conferred the freedom fighter certificate to him. I remember reading the article and I was amazed by it and much later when Ananth asked me to play the part, I was pleasantly surprised. It was an author-backed role, and in my opinion no actor in his right mind would let go of an opportunity such as this.”

The film has a very slow, quiet pace, acquiring speed in the flashbacks when Das looks back at his turbulent past as a teenager. The slow pace therefore, matches the slow and quiet rhythm of Das’s life initially. But the contrast between the pre-Independence, turbulent, arid zones of Balasore and the crowded lanes and bylanes of Mumbai in the post-independence 1970s bring out the contradictions in Das’ life, as do the shots constantly moving back and forth among different government offices, the security-framed bungalow of a minister, and the modest home of Das where he lives with his very supportive wife and angry neighbours.

This is a rare film where the director and the actors had the golden opportunity of interacting directly with the protagonist in real life. Commenting on how the meetings impacted his portrayal, Pathak says, “Meeting Mr Das several times helped me understand him and the person I was going to portray as a character in the film. What impressed me the most was his simplicity. He is the one of the most unassuming, simple-hearted, straightforward, genial and jolly man I've ever met. It was important to understand him and the pathos we were dealing with. Mr Das was a tremendous help in the making of the film, not only for me but for all of us.”

On what made him choose Vinay for the title role, Ananth says, “I wanted a lead actor whose personality would not be too dominant on screen. He had to look vulnerable and feeble, yet possess an inner strength that could shake up an establishment. Vinay studied Das closely and interpreted him without impersonating him. And that was a triumph for him as an actor. He has done a splendid job.”

A shot from the film showing the lead actor Vinay Pathak as Gour Hari Das. Pic: Ananth Mahadevan

However, Vinay does not look either ‘feeble’ or ‘vulnerable’ at any point through the film. But this invests him with the quiet, subdued and intense inner power that he draws from within, without making a noise about it. He most certainly does not look 70 with that peaches-and-cream complexion and skin smooth enough to model for face creams. But the portrayal is so controlled that these small lapses are undercut by the brilliance of the performance.

The other lapse is the too-clean image given to the Chief Minister. Neither in terms of accessibility, nor in terms of behaviour and attitude can one identify any Maharashtra CM with the image that this film gives him. This defines a tiny dent in the credibility of the character and the logic of the film.

One poignant touch is when the head of security at the home minister’s residence approaches Das holding his little boy’s hand. He says, “I have never seen anyone who was so close to Gandhiji in my entire life. He holds out a piece of cloth and requests him to spin a shirt for his little boy. Das quietly takes the piece of cloth. After this, the camera often cuts to Das at his spinning outfit weaving the shirt.”

Incidentally, the same head of security had been sceptical when Das approached him, seeking a meeting with the home minister. When asked what his name was, Das, with a poker face, had said, “Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.” The guard used the name over the intercom and later expressed his doubts to his junior about whether this man’s name was really what he had said it was!

The film is dotted with pot-shots at how the system has changed from commitment to corruption. “Why are you running after State pension, sir? I can arrange for Central pension,” says a tout pointing out that pension for freedom fighters can be bought through touts. In another scene, a journalist informs his colleague that after the freedom fighters’ pension had been raised, the number of applicants had increased from 16,000 to 53000. “It has become a business,” he adds dejectedly.

The film revolves entirely around Gour Hari Das. He is like a solid tree from which the branches of interesting characters emerge to add to his story. The supporting cast – the crazy journalist Rajiv who is convinced that there is indeed a ‘story’ in this man’s struggle, is amazed because Das is so different from what he himself is. Rajiv’s turbulent phase in life -- a bad marriage and divorce, uncertainty over his relationship with his girlfriend, his constant fights with his editor who wants ‘masala’ as news – complements and contrasts the drama in Das’s life.

Das meanwhile appears unperturbed by what is happening and does not once grumble about the blocks that he encounters at every step. His wife Laxmi is very supportive too, but worried about his failing health.

Konkona Sen as Das’ wife, Rajit Kapoor as a no-nonsense, hard-talking lawyer who means well, Tannishtha Chatterjee as Rajiv’s colleague-girlfriend, Ranvir Shorey as Rajiv, and Vikram Gokhale as the CM give wonderful support to Das in his struggle within the film and to Pathak who essays the role. The music is low-key and never dominates the scenario.

The climax is an eye-opener and almost an anti-climax for Das’ struggle, but then it has been fictionalised and is not what happened in reality. The CM invites him and hands him the tamra patra. “The government cannot afford a copper plate (Tamra Patra), so this is on paper,” he says.

Das takes a look at it, puts it back in the envelope and walks out gently. He finds a massive rally on the streets filled with men, women and children holding black flags, demanding ‘freedom.’ Das walks along with the rally participants. He spots a little girl beside him, hands the envelope with the certificate to the girl and walks away.

“The final procession of the new freedom movement was a cinematic depiction of Das' belief that the country needs a new revolution. Instead of merely mouthing these words, we gave it a larger picture, literally. The film has been a life changing experience for me. The tremendous feedback from India, London, Paris, New York, San Francisco and Canada festivals has been extremely rewarding and motivating,” sums up Ananth.