HIGHLIGHTS OF THE BILL

(Read this section in detail)

-

The Food Safety and Standards Bill, 2005 consolidates eight laws governing the food sector and establishes the Food Safety and Standards Authority (FSSA) to regulate the sector.

-

This page is organised as follows: The highlights of the Bill and the key issues to be considered are listed briefly first; the details of each are presented thereafter. Click here to see the highlights in details, and here to see the detailed analysis of key issues. FSSA will be aided by several scientific panels and a central

advisory committee to lay down standards for food safety.

These standards will include specifications for ingredients,

contaminants, pesticide residue, biological hazards and labels.

FSSA will be aided by several scientific panels and a central

advisory committee to lay down standards for food safety.

These standards will include specifications for ingredients,

contaminants, pesticide residue, biological hazards and labels.

-

The law will be enforced through State Commissioners of Food Safety and local level officials.

-

Everyone in the food sector is required to get a licence or a registration which would be issued by local authorities.

-

Every distributor is required to be able to identify any food article to its manufacturer, and every seller to its distributor. Anyone in the sector should be able to initiate recall procedures if he finds that the food sold had violated specified standards.

KEY ISSUES AND ANALYSIS

(Read this section in detail)

-

The organised as well as the unorganised food sectors are required to follow the same food law. The unorganised sector, such as street vendors, might have difficulty in adhering to the law, for example, with regard to specifications on ingredients, traceability and recall procedures.

-

The Bill does not require any specific standards for potable water (which is usually provided by local authorities). It is the responsibility of the person preparing or manufacturing food to ensure that he uses water of adequate quality even when tap water does not meet the required safety standards.

-

The Bill excludes plants prior to harvesting and animal feed from its purview. Thus, it does not control the entry of pesticides and antibiotics into the food at its source.

-

The power to suspend the license of any food operator is given to a local level officer. This offers scope for harassment and corruption.

-

It appears that state governments will have to bear the cost of implementing the new law. However, the financial memorandum does not estimate these costs.

Context

The food sector in India is governed by a multiplicity of laws under different ministries. A number of committees [2], including the Standing Committee of Parliament on Agriculture in its 12th Report submitted in April 2005 [3], have emphasized the need for a single regulatory body and an integrated food law.

The Food Safety and Standards Bill, 2005, aims to integrate the food safety laws in the country in order to systematically and scientifically develop the food processing industry and shift from a regulatory regime to self-compliance. As part of the process of consolidation, the Bill proposes to repeal eight existing laws related to food safety*.

Key features

-

Regulatory authority

The Bill proposes to establish the Food Safety and Standards Authority of India (FSSA), which would lay down scientific standards of food safety and ensure safe and wholesome food. The FSSA would be assisted by a Central Advisory Committee, a Scientific Committee and a number of Scientific Panels in specifying standards. The standards would be enforced by the Commissioner of Food Safety of each state through Designated Officers and Food Safety Officers.

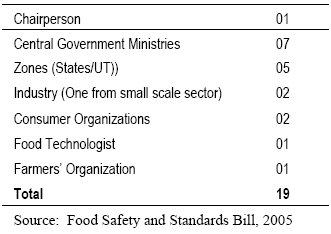

Table: Composition of FSSA

Table: Composition of FSSA

The FSSA would consist of a Chairperson and 18 members. The Chairperson would be either an eminent food scientist or a civil servant not below the rank of Secretary. Seven of the members would be ex-officio, not below the post of Joint Secretary, from various ministries. Five members would be appointed by rotation every three years from the states and Union Territories. The Authority would have two representatives each from the food industry and consumer organizations, one food technologist, and one member from a farmers' organization.

-

Standards for Food Articles

The Bill prohibits the use of food additives, processing aid, contaminants, heavy metals, insecticides, pesticides, veterinary drugs residue, antibiotic residues, or solvent residues unless they are in accordance with specified regulations. Certain food items such as irradiated food, genetically modified food, organic food, health supplements and proprietary food cannot be manufactured, processed or sold without adhering to specific regulations.

The Bill makes it mandatory for the distributor of a food article to identify the manufacturer and the seller to identify either the manufacturer or the distributor of a food item. Every packaged food product has to be labelled as per regulations in the Bill. The packaging and labelling of a food product should not mislead consumers about its quality, quantity or usefulness.

-

Food Recall Procedures

The Bill has special provisions for food recall procedures. If a food business operator (i.e., anyone owning or carrying out a business relating to food) considers that a food item is not in compliance with the specified standards, he has to initiate procedures to withdraw the food in question and inform the competent authorities.

-

Enforcement

Every food business operator is required to have a licence in order to operate his food business. Petty manufacturers who make their own food, hawkers, vendors or temporary stall holders do not require a licence. Instead, they need to get their businesses registered with the local municipality or Panchayat.

The Bill empowers the FSSA and State Food Safety Authorities* to monitor and regulate the food business operators. The Commissioner of Food Safety of each state appoints a Designated Officer (DO), not below the level of Sub-Divisional Officer, for a specific district whose duties include issuing or cancelling licences, prohibiting sale of food articles that violate specified standards, receiving report and samples of food articles from Food Safety Officers and getting them analysed. The DO also has the power to serve an 'improvement notice' on any food operator and suspend his license in case of failure in compliance with such a notice. The DO also investigates any complaint made in writing against Food Safety Officers. Food Safety Officers are appointed for a specified local area and their duties include taking samples of food articles, seizing food articles that are of suspect quality or inspecting any place where food articles are stored or manufactured.

The State Commissioner, on the recommendation of the Designated Officer, decides whether a case of violation would be referred to a court of ordinary jurisdiction or to a Special Court. Cases relating to grievous injury or death for which a prison term of more than three years is prescribed are tried in Special Courts.

The Bill provides for a graded penalty structure where the punishment depends on the severity of the violation. Offences such as manufacturing, selling, storing or importing sub-standard or misbranded food could incur a fine. Offences such as manufacturing, distributing, selling or importing unsafe food, which result in injury could incur a prison sentence. The sentence could extend to life imprisonment in case the violation causes death. Petty manufacturers who make their own food, hawkers, vendors or temporary stall holders could be fined up to Rs 1 lakh if they violate the specified standards.

In order to judge cases related to breach of specified regulations, the state government has the power to appoint an Adjudicating Officer, not below the rank of Additional District Magistrate. Any person not satisfied by the decision of an Adjudicating Officer has the right to appeal to the Food Safety Appellate Tribunal (or to the State Commissioner until the Tribunal is constituted). The Tribunal enjoys the same powers as a civil court and decides the penalty in case of non-compliance with the provisions of the Act.

-

Finances

The Financial Memorandum of the Bill estimates that an expenditure of Rs 10 crore is required to establish the FSSA. The amount includes non-recurring capital expenditure of Rs 3 crore and further recurring expenditure of Rs 7 crore per annum towards salaries, allowances, rent for office accommodation etc.

PART B: KEY ISSUES AND ANALYSIS

-

Objectives of the Bill

The main objectives of the Bill are: (a) to introduce a single statute relating to food, and (b) to provide for scientific development of the food processing industry. The Bill aims to establish a single reference point for all matters relating to food safety and standards, by moving from multi-level, multi-departmental control to a single line of command. It incorporates the salient provisions of the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act 1954 and is based on international legislations, instrumentalities and Codex Alimentarius Commission [4] (Codex).

-

Scope

-

Organised vs. Unorganised Sector

There could be a case for a separate regulation for the unorganised sector. Given that the unorganised sector includes a large number [5] of street food vendors, hawkers, temporary stall holders etc., application of the same law as for the large scale industries may be unrealistic, especially in the short term. Also, requirement of registration and powers given to local level officials to penalise infringement of required standards may lead to corruption. Some of the issues faced by vendors are addressed in the National Policy on Urban Street Vendors, 2004 formulated by the Ministry of Urban Development and Poverty Alleviation. [6]

Food hawkers in India are generally unaware of food regulations and have no training in food-related matters. They also lack supportive services such as water supply of adequate quality and rubbish disposal systems, which hamper their ability to provide safe food. [7] If such facilities were provided to food vendors, as has been done in countries such as Malaysia and Singapore [8], India might be more successful in ensuring that this sector is able to maintain acceptable standards of hygiene and cleanliness.

The Bill makes provision for graded penalties where offences like manufacturing, storing or selling misbranded or sub-standard food is punished with a fine and more serious offences with imprisonment. For instance, the penalty for manufacturing or selling sub-standard food extends to Rs 5 lakh, while for misbranded food, it extends to Rs 3 lakh. The Bill also makes provision for compensation in case of injury or death of the consumer. The street food vendors and hawkers can be fined up to Rs 1 lakh. The fines might prove to be debilitating for the unorganised sector and small scale enterprises, whereas such penalties might not be an effective deterrent for large companies.

-

Potable water

Though standards are specified for water used as an input in manufacture/preparation of food, the Bill does not require any specific standards for potable water (which is usually provided by local authorities). Thus, it is the responsibility of the manufacturer to ensure that clean and adequate quality water is used even when tap water does not meet the required safety standards. This could be a tall order given the scale of operation of small food enterprises and street food vendors. Cost of preparing food could also rise if each vendor or manufacturer has to invest in water purification systems.

-

-

Definitions

Some terms in the Bill have not been defined. This could create confusion and require interpretation by the courts in case of dispute.

The Preamble as well as Clause 16 (1) refer to 'safe and wholesome food' for human consumption. However, 'wholesome' or 'safe' have not been defined in the Bill.

The Bill also mentions certain terms like 'Food Safety Management System' whose definition calls for adoption of 'Good Manufacturing Practices', 'Good Hygienic Practices' and 'Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Point'. However, it is not clear from the Bill what these terms imply and whether the Codex definition of such terms is to be followed.

In the Bill, 'Contaminant' is defined as 'any substance, whether or not added to food, but which is present in such food as a result of production, manufacture, processing, preparation'. The Codex guideline, on the other hand, defines contaminant as 'Any substance not intentionally added to food, which is present in such food as a result of the production' (emphasis added). The omission of the phrase 'not intentionally' from the definition in the Bill could result in cases where yeast added to bread might be called a contaminant.

-

Implementation and enforcement

-

Managing Pesticide Residue

The Bill excludes plants prior to harvesting and animal feed from its purview. Any harmful input (such as pesticides in vegetables or antibiotics in animal feed) that could affect the safety standards of food products are not effectively covered. Therefore, the onus for ensuring that pesticide residue is within acceptable levels lies with every manufacturer/vendor.

-

Traceability

As per Codex guidelines, traceability covers the whole chain from the farm to the consumer. However, in India, many items such as grain and vegetables are sold at mandi (wholesale) markets. If a food product contains grain or vegetables with pesticides above the permitted level, it would not be possible to trace back the contaminant beyond the mandi. This makes it difficult to take any corrective action.

-

Testing Facilities

The Bill states that samples of food articles would be sent for testing to various accredited laboratories. It also stipulates how many samples should be taken. However, shortage of testing laboratories and equipment [9] might hamper the implementation of the Bill. [See the section on Finances below].

-

Promote or Penalise

The Bill aims to provide for a 'systematic and scientific development of the Food Processing Industry'. However, the thrust appears to be on penalising offenders of food safety standards rather than providing support to improve their systems. Given the limited capital of many small scale food processors, there is a possibility that noncompliance could be due to lack of technical standards. Thus, there may be a case to provide support for improving systems within a reasonable timeframe, failing which penal action may be initiated.

-

Penalty Provisions

The DO has the power to issue an 'improvement notice' to any food operator, and suspend his license in case of non-compliance. Such power at the local level offers scope for harassment and corruption.

-

Consumer Safeguards

The Bill provides a safeguard for consumers with a provision for Food Recall Procedure. It states that if a food business operator considers that a food item which it has processed, manufactured or distributed is not in compliance with the Act, it shall immediately initiate procedures to withdraw the food in question and inform the competent authority. The Bill however does not require the food business operator to inform consumers about a product recall, especially if some of the products have already been sold.

-

Safeguards for Food Businesses

The Food Safety Officer, while taking food samples for analysis, has to give one part of the sample to the food business operator to make available to the authorities. Providing the food business operator with the right to get the sample tested independently from an accredited laboratory could reduce opportunities for harassment and corruption.

Any customer can get an article of food examined by a Food Analyst. If this sample is found to be in violation of specified standards, penal action can be initiated. This power in the hands of the customer can be misused.

-

Labelling

The Bill does not specify details about labelling, and leaves it to the regulations which will be issued by the FSSA. However, there is a view that certain items are important enough to be specified in the Bill such as labels identifying Genetically Modified food and labels detailing nutrition content in packaged food.

-

-

Composition of the FSSA

There are two issues relating to the composition of the FSSA. The first issue relates to the representation of the Authority. One could argue that there should be a wider representation from various industry sectors (such as fruit and vegetables; meat and poultry products; milk and milk products; marine products; pickles and jams) as well as from restaurants and street vendors. A counterpoint is that a regulatory body should not have direct representatives from the businesses that it regulates in order to reduce possibility of conflict of interest, and there should be only independent experts and civil servants in the Authority (similar to regulatory bodies such as Securities and Exchange Board of India, Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, and Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority). Similar arguments can be made with respect to the composition of the Central Advisory Committee, which comprises two representatives each from the food industry, consumers, agriculture, and relevant research bodies in addition to all 35 state Food Commissioners.

The second issue is whether all members should be whole time members, given the substantive nature of the responsibilities. This applies, in particular, to the central government representatives who are ex-officio members with additional responsibilities.

-

Finances

The Financial Memorandum of the Bill estimates non-recurring capital expenditure of Rs 3 crore and further recurring expenditure of Rs 7 crore per annum towards salaries, allowances, rent for office accommodation etc. The Bill mentions that the FSSA would charge a fee from licensed food operators and accredited food laboratories. However, the question remains whether the funds would be sufficient to maintain the infrastructure required to implement the provisions of this Bill, which include setting up laboratories, training food safety officers and running awareness/training programmes for food business operators and consumers.

The Financial Memorandum does not specify whether the cost of implementing and enforcing the provisions of the Bill would be different from the existing system under the Prevention of Food Adulteration Act of 1954 (PFA Act). A comparison of the cost of enforcement under PFA Act and the new system proposed by this Bill would be useful in estimating the net cost implications of this Bill.

It appears that the cost of enforcement would be borne by state/Union Territories governments. It would be useful to estimate the cost that would be incurred by state governments for setting up the required system.