|

|

Environmental interventions must not merely serve to transfer risk from one social group to another, writes Ravi Agarwal.

July 2002: Fairness and equity have not always been a part of the process of environmental protection. Environmental improvement is considered by many to be a simple question of using the right technology to clean-up and reduce pollution. It is not instantly obvious that such a clean-up could be the cause of a problem somewhere else. It is therefore important to understand the manner in which society is divided and to track the most socially and economically disempowered social group to find the invisible trace of the shift.

Human existence is caught in a power play of hierarchical social structures. The questions relating to the environment and basic issues of resource usage and resource distribution, as well as the human interdependencies this creates are interlinked. Those who are part of the least socially (and often economically) powerful groups are often also the most vulnerable.

If environmental change does not recognize and question the inequity of such hegemony, then at best it may effect a pocket of change, while at the same time pushing the problem to another place. Environmental interventions have to be examined not only through their immediate visible impact, but also in the larger context of how they change the lives of those who may not be directly visible. Action needs to be driven by a strong understanding of what is just and fair and not merely serve to transfer risk from one social group to another.

At the same time, one must examine the nature of decision-making in the environmental change process. Here, the institutions that initiate and deliver change too need to be investigated. Who owns them, and whose interest do they really represent? Equitable change may be most effectively deliverable through institutions that are democratic, such as representative grassroots organizations, and which are made up and controlled by those who have an immediate stake in the local environment.

Whose World is it Anyway?

People involved in environmental change first need to answer the question: "Whose environment?" Can solutions to a cleaner and more sustainable environment be developed without accounting for those who are impacted the most? Can fairness and equity be guaranteed without true democratic consultation? Do people really have a choice even when they lack the capacity to make informed decisions?

In India, there has been hardly any reflection on environmental problems at the political level. Subsequently, environmental policy is often been drawn in isolation to the ground reality, owing to the inadequate voice of the victims. This is particularly relevant today when millions of powerless people are being placed at environmental risk through being displaced, toxified or rendered jobless in the new economic order.

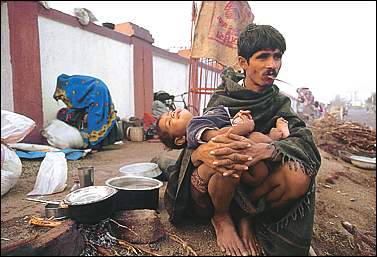

|

| Life at the bottom rung |

Take the example of waste. Often, those who generate the most waste are guilty of dumping it on those who are at the bottom of the economic ladder, with little social and political influence to better their lives. In the U.S., California state, spurred on by local environmentalists, set recycling goals of 50 percent. The collection spree generated far more plastic (like PVC which is not only hazardous but difficult to recycle) than could be handled. Much of this was, and continues to be, shipped to India and Bangladesh.

Typically, the trader who buys the imported consignment auctions it to backyard recyclers at the port itself. From there, along with locally generated plastic waste, it travels to urban slums, where underpaid, undernourished adults and children breathe in toxic fumes emitted during the recycling process. All this, in a bid to make countries like India the 'recycling capital of the world,' with a 60 percent recycling rate!

Good environmentalism or plain injustice?

Political Callousness Abets Inequity

The state abets such a movement as an economically beneficial one. Units in India have been allowed to import plastic waste as a business simply because the material has not as yet been classified as 'hazardous waste' under international norms. The shifting of the risk in not merely from one affluent country to a poorer one, but to the poorest in that land.

Can we treat the two issues of waste and the lives of the people dealing with it, as separate? For most of us, waste out of sight, is out of mind. Yet, for the poor who collect and handle it, it means a toxic livelihood. If we try and find conventional environmental solutions then the burden only shifts. Down the economic ladder. The risk of ill health transfers itself from the city center to its periphery in the form of landfills and waste dumps. Socially, the problem has shifted to the deepest hole, and everyone along the way has helped it get there.

Inequitable environmental solutions are not limited to issues of waste alone. In 1997, the Supreme Court of India ordered that all polluting industries in Delhi – mostly small units – be relocated outside the city. This judgement put the jobs of thousands of migrant industrial workers – who had, in the first place, moved out of their villages to Delhi in search of jobs – at risk. The workers, mainly casual, daily wage earners, did not stand to gain from the compensation package as they had never registered on official rolls and therefore, did not exist. Also, the relocated industries would only end up polluting the countryside on which lies large tracts of agricultural land.

|

| Workers bear the brunt of occupational and industrial risks in unprotected working environments, as well as job insecurity through inappropriate environmental action. |

Or take the case of shipbreaking. Old ships laden with toxins like lead-based paints, PCBs in transformer oils and asbestos in their worn-out lining, are sent to India from Europe, U.S.A. and Russia for breaking, to Alang shipyard in Gujarat state. With a 40,000-strong workforce, Alang breaks half the world's ships. Not only is the job of dismantling a highly hazardous one, but the toxins from the ship lie spewed all over the beach and endanger marine life. The developed world refuses to break its own ships. Once more, risk has been successfully transferred to those who do not count. And for middlemen like the trader, only economic gains seem to matter. The killing fields of Bhopal did not move either Union Carbide or the Indian state to care, in one of the worst industrial accidents ever known. In 1984, the local Union Carbide factory, sited beside a heavily populated area, leaked a deadly gas, MIC, killing over 5,000 people within a few hours, leaving over 200,000 struggling for their lives even to date. The problem? Callous operating procedures in a country with lax environmental and safety laws and no obligations to inform the local population of the nature of the processes. The multinational giant would never had dared to run their factory in the developed world in quite the same, irresponsible way. Risk shifting in this case also prompted the company to shell out a fraction of the compensation they would have had to pay had the accident occured in the U.S.

Technology as the Bogeyman

Often, technology is cited as the answer to what seem to be insurmountable problems. However, technology is not necessarily democratic either in the problems it addresses or the people who are able to access it. It is not automatically fair and equitable by itself, and can be selective in its impact. Millions of people, for instance, have been displaced through large power projects, including dams, for water and electricity they will never ever receive.

Appropriate technology, a term that has come to imply technology for the greater common good has remained a shibboleth and has not helped in mitigating risk for the poor. Technical solutions do not necessarily address the most pressing problems of the poor. For example, rural women in India are exposed to many times more air pollution indoors – because of wood fires used for cooking – than city folk are, out on the roads. But while adopting the latest clean automobile engine technology is touted as an achievement, making kitchens smokeless is not in the same order of priority.

Technology for one can be a curse for another. In early 2000, farmers who have lived and carried out agriculture for decades, in what is now the green belt of the modern city of Delhi, protested against the setting up of a hi-tech hazardous waste landfill in their neighborhood. This was to accommodate the city's waste, largely generated by its middle class. Designed to 'high international standards,' the landfill would usurp fertile land and the green belt, and make their neighborhood a dumpyard. Groundwater, on which they largely depend on for drinking, would get contaminated. A classic case of one man's waste becoming another man's poison.

In other cases, technology can directly shift the risk to those who are socially less empowered. Indian municipalities are in a frenzy to find a quick-fix solution to the growing mounds of waste, and are proposing the installation of waste incinerators, to be located in the poorest urban neighborhoods. There is little concern that those who live in the vicinity of these monstrous machines will be those worst affected by exposure to toxins, which enter the food chain through air and water.

Technology usage and its application is market driven rather than socially driven. Dirty air in India became an issue only after the middle class started to realize its impact and technofixes in the form of upgraded motor engines and cleaner fuels are following. The poor, on the other hand, have long waded in sludge, excreta and soot, but there is no commitment to constructing simple toilets, or bicycle tracks on the chaotic and dangerous city roads.

Power Play Marginalizing the Disenfranchised

Environmental policy in India has only reinforced many of the above biases by not attempting to involve the economically weak, directly or through institutional reform. Indian industrial siting laws legislate against the setting up of industry close to cities, but are lax on their being located in farmland. Urban pollution linkages are cited as a reason, but no government data has been collected to show the detrimental effects of pollution on crop productivity, though this is a known fact. Industrial sludge is piped into rivers, sometimes in agreement with environmental groups looking for immediate solutions, out of sight from urban centers, regardless of its effect on fisher folk and resultant fish kills. Waste solutions have involved better collection and disposal, but with no emphasis on improving the lot of the ragpickers and recyclers.

The conflict between jobs and the environment is an old one, but is increasing with the changing power balance between those who represent either interest. More has to be done to define common viewpoints and to attempt to create partnerships, no doubt in complex and seemingly contrary concerns. For example, workers have simply not been recognized as possible key stakeholders for environmental change, giving rise to unnecessary fissures between labor and environmentalists, in what should be a common fight essentially rooted in common values.

|

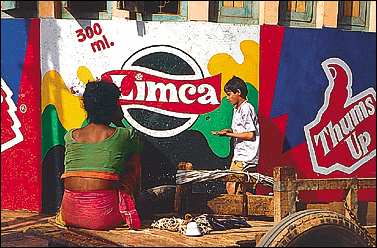

| Thumbs up for globalization? |

The globalization of capital and technology is pushing to marginalize trade unions and the environment is becoming increasingly appropriated, without embodying it into true institutional reform. Companies are increasingly cashing in on the 'feel good' value in the marketplace by claiming that their products are, for example, recyclable or environmentally friendly. Claims, which if examined, may not hold. Sustainable development is the new catchword, though the term itself defies a definition if it is not placed in the context of equity and fairness.

True environmental sustainability also need to be humanly sustainable. The values that we enshrine need to find place in our everyday work. We need to recognize our true partners – be they the poor, laborers, slum dwellers or villagers – and forge collaborations with them. Environmental solutions are inextricably linked to human solutions and human justice. There do not have to be any 'big' answers, but there can be many immediate small ones.

True environmental solutions have to improve the lives of the majority, and not restrict them further. They have to be rooted in a democratic ethos. They must have a human face. A face of those who are faceless.

Ravi Agarwal

June 2002

Ravi Agarwal has been working as an environmental activist in the area of waste, toxicity and urban planning and environmental interfaces for the past decade. An engineer with a management background by training, he quit the corporate world, spurred on by unfair moves to usurp Delhi's urban forests – it's lungs – by land developers. He is the director of Srishti, a New Delhi-based NGO. Through Toxics Link (www.toxicslink.org), he is asscociated with a national information network, geared toward grassroots groups fighting toxics in the country, besides being involved in the process of national and international policies related to these areas.

Agarwal is also a keen photographer and has held one-man photo shows on street dwellers and labor. He has recently published a photo-book on migrant labor in Gujarat, India, published by Oxford University Press. Agarwal lives in New Delhi, India. This article comes to India Together by arrangement with Changemakers.net. It was originally published in the Changemakers Journal.