•

Write the author

Consequently, instead of promoting constitutional aspirations, India is forced to make its legislations by referring to the aims and

objects of such legislations, the executive commitments made at WTO. One such illustration - there are many, such as the Patents

Amendment Act - can be made of the "Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers' Rights Act, 2001". The preamble to this Act states:

"And Whereas, India, having ratified the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights should, inter alia, make

provisions for giving effect to sub-paragraph (b) of Paragraph-3 of Article-27 in Part-II of the said Agreement relating to protection of

plant varieties".

In the Constitutions of many other countries, we provisions where the treaty becomes binding only after

it is cleared by the majority of People's Representatives in the Senate/Assembly/Parliament.

This Act of the Parliament clearly shows that the interests of our farmers and our agricultural biodiversity which is protected under the

Constitution (Articles-21, 48 and 48A) has been subjected to the provisions of TRIPS. If the Constitution is supreme then such

legislations cannot and should not survive, unless they answer the test of being in conformity with the constitution. It is the duty of

Parliament to tell people how such legislations can subserve common good, protect people's rights, farmer's rights, our agriculture, our

biodiversity, etc. Under the oft-repeated slogan of development, the people's rights given to them under the Constitution cannot be

defeated.

A comparison between India and the US

The treaty-making power under our Constitution has been given to the Executive under Article-73. Article 246(1) read with Entry 14 of

List-I Union List of the Seventh Schedule empowers Parliament to make laws with respect to "Entering into treaties and agreements with

foreign countries and implementation of treaties, agreements and conventions with foreign countries". Article-253 gives powers to

Parliament to make laws for the whole or any part of the country for implementing any treaty, agreement or convention. Article 253 has,

thus been given an overriding power. Empowered by Article-73, an Executive, without any debate in the Parliament or assent of the people

in any discernible way, can commit itself and surrender people's basic and fundamental rights and thus bind the country to enact

legislations, which go against the basic principles of our Constitution and aspirations of the people.

In contrast to this process, in the US Constitution, the President has been given power to make treaties by and with the advice and

consent of the Senate provided two-thirds of the Senators present concur (vide Article-2 (2). It may also be pointed out that US has made

it clear that none of the decisions of WTO, which are contrary to their law and Constitution, will be binding on the American people.

Section 102(a) of Uruguay Round Agreement Act reads as follows: "Section 102(a) ( a )Relationship of Agreements to United States

Law: (1) US Law to Prevail in Conflict : No provision of any of the Uruguay Round Agreements nor the application of any such provision to

any person or circumstance, that is inconsistent with any law of the United States shall have effect."

America has thus, fully protected its sovereignty and the rights of its people. Even in the Constitutions of other countries, namely, in

South Africa, Republic of Korea, the Philippines and so on, we find provisions similar to US where the treaty becomes binding only after

it is cleared by the majority of People's Representatives in the Senate/Assembly/Parliament, as the case may be.

Therefore the question which arises is whether the commitment made by our Executive without the people's support can bind us when we have

accepted the Constitutional supremacy. The answer, again in the opinion of Justice Iyer, is "No". He says in the same book, Off the

Bench: "Democracy, by participation of the people directly or through their surrogates, is a basic feature of the Constitution. So,

it follows that a treaty which has neither the sanction of a referendum or ratification by Parliament (Senate ratification is vital for a

treaty in US.) is non-est. If the Bommai case is good law the TRIPS treaty is perilously near invalidity."

States' jurisdiction versus the Centre

Furthermore, legislation pursuant to the treaty obligations, can totally deny the participation of States in such legislative process

when the subject matter (for example, agriculture or fisheries) squarely falls within List-II, the States List. Taking note of this

serious lacuna affecting the federal character of the Constitution and powers of the State to legislate within the domain of List-II, the

National Commission to Review the Working of the Constitution in its report recommended that in the decision making on important issues

involving the States, prior consultation should be done with the Inter-State Council before signing of the treaty. The Commission thus

endorsed the view of the Sarkaria Commission on Centre-State Relations. In fact, if the federal nature of our Constitution is a basic

feature, all the legislations which take away the rights of the States suffer from a basic infirmity.

The solution, however, does not lie in discussions with the Inter-State Council but in taking away the power to sign or ratify any treaty

from hands of the Executive.

It is only after the Executive is empowempowered by Parliament through majority that such treaties should be

signed or ratified.

There is yet another aspect which needs to be addressed. In various judgments, the Supreme Court has been relying on the

Treaties/Conventions, for example, those pertaining to human rights and environment, which elucidate and effectuate the people's

fundamental rights, in particular, Article-21 of the Constitution. Many of these Conventions/Treaties have been incorporated as part of

Article-21 of the Constitution. As far as the environmental principles forming part of various Declarations/Conventions are concerned,

they are accepted as part of the customary international law and thus incorporated in the domestic law and followed by the courts in the

absence of anything contrary in the municipal laws (vide Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India & Others, 1996 (5) SCC

647; PUCL vs. Union of India, 1997(3) SCC 433; RFSTE v. Union of India, 2003 (9) SCALE 303). In this case, the safeguard is

that the Constitution's supremacy has been upheld and nothing which is in derogation to the Constitutional mandate has been accepted.

It is only after the Executive is empowempowered by Parliament through majority that such treaties should be signed or ratified.

Sanjay Parikh

•

Vol #4, Issue #5, Combat Law

•

Trade

•

Laws

•

Printer friendly version

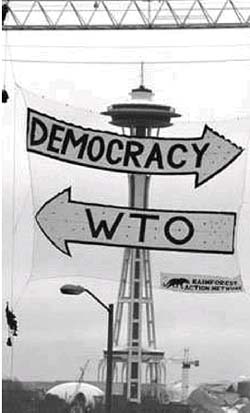

![]() Let the WTO's will be done?

Let the WTO's will be done?

"GATT is a calamity if the Constitution of India has validity", said Justice Krishna Iyer.

Sanjay Parikh

agrees, noting

that the lack of ratification by Parliament of decisions taken by India at the WTO

dilutes the separation of powers, and also treads on States' jurisdiction. This could have far reaching effects on

Indian legislation.

Combat Law, Vol. 4, Issue 5 -

When our founding fathers gave us our Constitution, we made a commitment to ourselves that we would uphold the Preamble, protect

Fundamental Rights and gradually bring into reality the people's aspirations contained in the Directive Principles. In all our

legislations before the 1990s, there is invariably some reference to the Preamble, Constitutional goals and the Directive Principles. But

after the Uruguay Round, India (through its executive) accepted the obligations in GATT/TRIPS, which is institutionalised in the form of

WTO, by signing the treaty in 1994. It did so without taking into account that it was making a commitment without the peoples' will.

•

Government or Parliament?

![]() This Act seeks to protect the rights of plant breeders, which only means the protection of multinational seed companies and taking away

the inherent rights of farmers over their seeds and traditional variety of their produce. In the Bill of the said Act, a complete go-by

was given to the farmer's rights. But, when NGOs' protested, it was referred to the Joint Parliamentary Committee, which attempted to

balance the rights of breeders as against farmers. The Act has not yet been brought into force, as quite surprisingly, it has been

submitted before the UPOV - a Convention that recognises and ensures the Intellectual Property Rights (IPRS) of the breeders' alone, when

admittedly India has chosen the sui-generis option.

This Act seeks to protect the rights of plant breeders, which only means the protection of multinational seed companies and taking away

the inherent rights of farmers over their seeds and traditional variety of their produce. In the Bill of the said Act, a complete go-by

was given to the farmer's rights. But, when NGOs' protested, it was referred to the Joint Parliamentary Committee, which attempted to

balance the rights of breeders as against farmers. The Act has not yet been brought into force, as quite surprisingly, it has been

submitted before the UPOV - a Convention that recognises and ensures the Intellectual Property Rights (IPRS) of the breeders' alone, when

admittedly India has chosen the sui-generis option.

![]() Parliamentary ratification should take supremacy

Parliamentary ratification should take supremacy

![]() If the executive action of signing GATT/TRIPS and consecutive compulsive legislations are tested on the constitutional anvil, they will

fail the basic judicial scrutiny. Are we thus left with the only option to challenge all the legislations - which are gradually taking

away people's rights under the cover of development and so-called international commitments - before the Courts, and that too under their

limited powers of judicial review and at times facing the argument of policy decisions where the Courts also raise their hands? Is this

scenario not unhealthy for a sovereign, democratic republic like India? The only hope lies in amendment to the Constitution.

If the executive action of signing GATT/TRIPS and consecutive compulsive legislations are tested on the constitutional anvil, they will

fail the basic judicial scrutiny. Are we thus left with the only option to challenge all the legislations - which are gradually taking

away people's rights under the cover of development and so-called international commitments - before the Courts, and that too under their

limited powers of judicial review and at times facing the argument of policy decisions where the Courts also raise their hands? Is this

scenario not unhealthy for a sovereign, democratic republic like India? The only hope lies in amendment to the Constitution.

Combat Law, Volume 4, Issue 5

(published 08 January 2006 in India Together)

•

Vol #4, Issue #5, Combat Law

•

Trade

•

Laws

•

Feedback :

Tell us what you think of this page.