The island of Jambudwip in the Sunderbans (West Bengal) became the issue of contention in November 2002 between the West Bengal State government and a unique fishing community in India, whose fish-drying activity which has been taking place on that island for the past thirty-five years. The fish-drying was seen not only as a threat to the mangrove forests on Jambudwip, but also to national security. This conflict resulted in the government burning down the large huts (which the it claimed were illegal godowns) of the fisherfolk on the island, and prohibiting them to set foot on it in the future.

On the face of it, this seems a case where conservationists, supported by the government, protected mangroves and wildlife in the Sunderbans from fisherfolk whose activities would have destroyed the island. But, as is so often the case in conservation struggles, things were not so simple.

Jambudwip is an isolated island situated in the Bay of Bengal about 8 km to the southwest of Fraserganj in the South 24-Parganas district of West Bengal. It remains uninhabited except in the fishing season, i.e. between the months of October and February, when the fisherfolk come for work. For a long time, about 10,000 fishermen have made a living by the seasonal fishing from October to February on the island. There is recorded history of fisherfolk using this island from 1955, in Bikash Roychaudhari's book The Moon and the Net - Study of a Transient Community of Fishermen at Jambudwip, published by the Anthropological Survey of India in 1967.

In the past, these fishermen came from the Chittagong and Noakhali areas of erstwhile East Pakistan. They developed special aptitude and traditional skills for marine fishing. The main reasons for using Jambudwip were the island's proximity to the fishing grounds, presence of a natural creek for safe harbouring of their boats, and supply of drinking water. With these pluses, Jambudwip became one of the bases for a unique transient fishing community. The temporary nature of the construction of their fishing camps on the island was understandable; their profession here was a wandering and seasonal one. Though the socio-economic composition on this island has changed, the other characteristics of their activities still remain the same.

Jambudwip island is a notified 'Reserve Forest' (1943) and out of the total area of the island comprising 1950 hectrares, the fishermen use approximately 300 hectares for their fish drying activity. The rest of the area has good growth of mangroves - which have been unharmed and kept intact by these fishermen for the past 35 years. The forest department of the Government of West Bengal has been issuing seasonal permits in lieu of prescribed fees to these fishworkers and they have also been issued forest passes to use dry fuel since 1968. Thus the Government for several decades has recognised the presence of these fishworkers, and that too well after the enactment of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972 and the Forest Conservation Act, 1980.

But suddenly from 1998 the forest department stopped issuing passes and discontent started brewing, leading to a confrontation between the forest department and the fisherfolk. Following the agitation by these workers, the Chief Minister of West Bengal intervened and requested the Ministers of the Fisheries Department and Forest Department to settle the dispute. Accordingly, on 9th August 2002, the concerned departments arrived at an agreement with certain restrictions to preserve the mangrove forest but allow the fish drying activity on the island. This should have resolved the conflict. However, the situation got aggravated in the coming months.

The reason: the conflict was also entangled in legal issues; in particular, with the legal juggernaut of T N. Godhavarman vs Union of India (Forest case). The Supreme Court, in that case, passed an order on 18.02.02 stating that the Chief Secretaries for various states, including West Bengal, are directed to file a reply to indicate what steps have been taken to clear the encroachments from the forests which had taken place earlier. This case has now become the gospel with which the States approach forest conservation without understanding the nuances of ecosystem approach.

On complaints lodged by environmental groups like the WWF and the Wildlife Protection Society of India (WPSI), the Central Empowered Committee (CEC) instituted by the Supreme Court to look into various complaints regarding encroachment of forest land, visited Jambudwip on December 3, 2002 and met the leaders of the fishworkers and others. The CEC in its report dated December 20, 2002, ordered the concerned authorities to evict the fishermen by March 31, 2003 and also imposed conditions on the applicability of the regularisation clause (that would allow the fishermen to continue their activity) of the Forest Conservation Act, 1980.

The CEC not only blamed the fisherfolk for mangrove destruction, but also said in their report that Jambudwip is a security concern and a haven for smugglers, poachers & illegal migrants! However, the District Magistrate (DM) of South 24 Parganas had after an enquiry in 1999 clearly stated that there were no illegal Bangladeshi immigrants on the island and it does not call for any unnecessary concern. The 1999 report was submitted both to the State Government and the Central Home Ministry. No incidents of smuggling, poaching, armed dacoity have ever been reported in and around the island. Nor has there been any arrest of illegal migrants or interception of contraband. Jambudwip is 96 km from the Indo-Bangla border - one of the furthest islands of the region.

The CEC had proposed in their report that fishermen should be given an alternative site at Haribanga or lower long sand island which is an isolated island with approximate an area of 200-250 ha. This island is still in its formative stage.

Mr. Pranabesh Sanyal (Additional PCCF) has stated that at one point of time he had moved a proposal to declare the Haribanga island a marine wildlife sanctuary. The same fact about the rich marine biodiversity in and around the Haribhanga island was reiterated by Prof. Amalesh Chowdhury.

So, it is rather odd that in the name of saving one island Jambudwip the CEC and MoEf is willing to settle 10,000 fishermen on a ecologically sensitive island which the State forest department considers worth declaring as a marine sanctuary.

• Big fish, little fish

In August 2003, the local fishermen association of Jambudwip along with National Fishworkers Forum appealed their case in the Supreme Court against the CEC report, seeking their traditional rights back. This case has been going on in the Supreme Court since 2003, due to which the fishermen have lost three crucial fishing seasons. This has left them desperate and they have been looking for other sources of livelihood. But, since many of them know no other skill other than their traditional fishing, it is difficult to find jobs other than being manual labourers.

There was an interim order dated 25th August 2003 stating "that no mechanised trawlers or boats would be allowed to enter Jambudwip and its neary waters. However traditional fishing boats would be allowed to dry fish as this would not seriously disturb the ecology of the mangrove forest" But despite this order fishermen were not even allowed to take their tradional boat and say they were chased and beaten up by the forest gaurds and policemen.

The court had ordered the Ministry of Environment and Forests and the State department to file their affidavits in this case.This March, the MoEF told the Supreme Court that it is rejecting the claim for regularisation of encroachment on the grounds of national security, and the adverse effect on mangroves. This is despite the fact that when in 2004, the same MoEF had filed an affidavit in the SC saying that if the State government agrees to give land on Jambudwip to these fishermen then the Ministry would have no problems with that. Whereas the State Gov agreed in 2004 itself on giving 100 ha land to these fishermen to continue their activity and also submitted that they are ready to give another 100 ha as a compensatory afforestation."

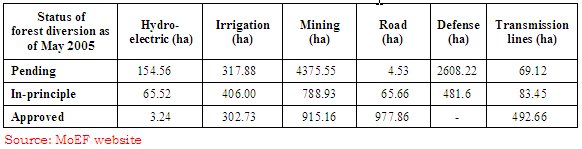

Meanwhile, the same MoEF fighting tooth and nail against giving 100 ha of land on an island to these fishermen, has not flinched from giving thousands of hectares of good forest land for various projects. See the table below for reference.

The fisherfolks' plight is a reminder of the tragedy of the government's role in conservation in India. None disputes the importance of forests, or of their conservation, but nearly all government interventions find it convenient to allot forest lands to industrial users, and deny the same to native people and traditional users. The government is also blindly insisting that the traditional uses are more damaging to the forests, although the evidence is clear that communities have managed their environment much better than corporations! Why do the local people always have to bear the cost for the greater common good?

The legal space is also complex. Many rights activists question whether one blanket act, (Forest Conservation Act-1980), and one judgement at the apex level can encapsulate the complex nuances of various ecosystems and the people in them. Do the laws provide a flexible mechanism by which diverse and dynamic conflicts can be dealt with? The "forms" of human livelihoods in the forests have evolved historically and mostly out of proximity of local or transient folks to different kinds of natural resources. Even the proposed new tribal bill may not be of help to these fishermen, as they are not tribals, but are equally dependent on natural resources for their basic livelihood. Also according to this draft Act the land distribution will be done by the gram sabha, which in case of Jambudwip has no meaning as these people only come to jambudwip for five months and leave after the season is over.

In Jambudwip the fishermen are ready to restrict their activity according to the carrying capacity of the island, and be part of any conservation effort by the government, but the forest department is unwilling, they say, to provide the space for that discussion.

A proper and scientific impact assessment of the fishermen community (10,000 people) on the mangrove system may provide some answers. If the impact on the mangrove system is minimal or negligible, then the issue of enforcing of the Forest Conservation Act could only be justified through principle - and enforcement of a law simply for the sake of principle becomes senseless when so many livelihoods are at stake. However, if the impact is negative or destructive, then these people's dependance on the mangrove system would need to change, and that would require a serious reengineering of their livelihood.